Ah,

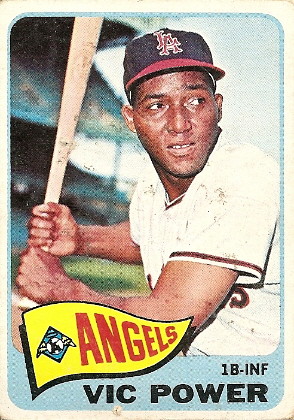

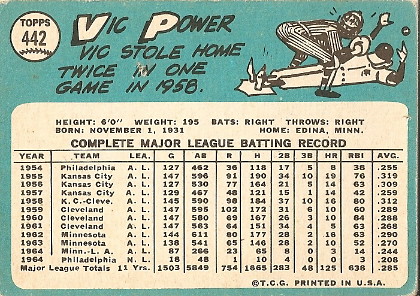

Vic Power, one of the greatest baseball names there ever was. Sure, his single-season high was 19 home runs, placing him behind such notable sluggers as Mike Bordick and Davey Johnson, but power is not just about four-base hits. It's a lifestyle. No one embodied that lifestyle, particularly on the diamond, like Vic Power. I like to think of his name as a rallying cry for Vics everywhere: "Vic POWER!".

Victor Pellot Pove grew up in Puerto Rico, and honed his skills playing for the San Juan Senators (or Senadores) in his early twenties. In 1949, he moved to mainland North America and played for a professional team in Quebec. Wikipedia (yeah, I know) suggests that French-Canadian fans snickered at Vic's name (he went by Pellot, his father's surname). There's no sourcing, of course, but my crack Internet research leads me to believe that "pelote", the French word for "ball", could have easily been a source of amusement for the terminally immature. So it was that he began going by his mother's maiden name, "Pove", which was roughly translated to the English "Power". Sheesh, talk about getting bogged down in linguistics.

Vic soon caught the eye of Yankees scouts, who signed him in 1951. The notoriously slow-to-integrate pinstripers seem to have been put off by the unapologetic nature and sharp wit of the young first baseman. During his first season in their organization, he reportedly entered a restaurant and was informed that they did not serve colored people. He

replied, "That's OK, I don't eat colored people. I just want rice and beans." Despite hitting .331 with 109 RBI in the minors in 1952, Power was not invited to the major league camp the following Spring. The writing was on the wall, and indeed New York traded him to the Athletics as part of an eleven-player deal in December of 1953. A popular rumor has the Yanks deciding to dump Vic because he had been dating a white woman.

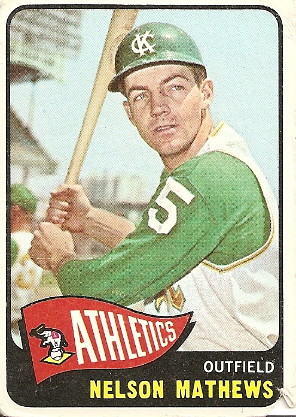

Whatever the circumstances, Power was finally a big leaguer in 1954, at age twenty-six. In the last season for the woeful A's in Philadelphia, he became the club's first Puerto Rican player. But it wasn't until they moved to Kansas City that the first baseman truly announced himself as a force. 1955 would hold up as the finest performance of Vic's career - he was an All-Star and a top-ten vote getter in the MVP race. He hit .319 with 61 extra-base hits and 76 RBI. Despite a dip in power the following season, his batting average stayed strong at .309 and he returned to the All-Star Game. Following a disappointing 1957, the A's shook things up in June 1958 by trading Power and Woodie Held to Cleveland for Roger Maris and two other players. The newest Indian responded by finishing the season at .312 overall with a personal-best 37 doubles and league-leading 10 triples. He also won his first Gold Glove.

Vic Power attracted lots of attention with his flashy play in the field. At the time, it was unheard of to catch the ball one-handed at first base, and it quickly became his calling card. Of course, now we take it for granted that this style of play increases flexibility and range, but Vic was instrumental in redefining his position. He was also an All-Star in two of his three full seasons with the Tribe, combining his doubles power with batting averages in the high .280s and continuing his slick work with the leather.

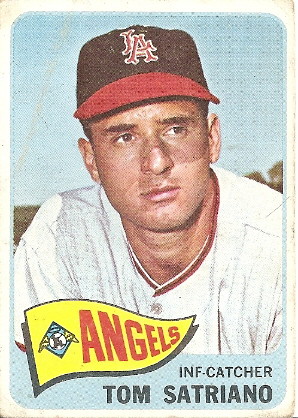

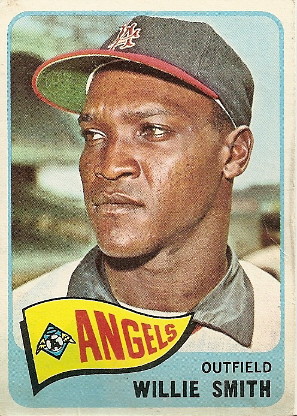

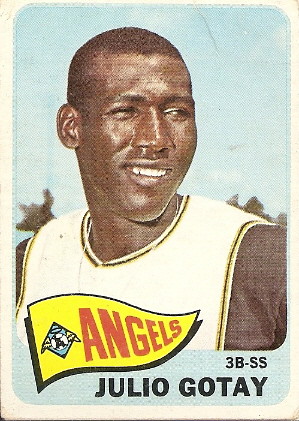

On the eve of the 1962 season, Power joined the Twins via another trade; pitcher Pedro Ramos was the outgoing Minnesota player. Again looking to make a good first impression, the first baseman was selected as the team's standout player of the year on the strength of a .290, 28 2B, 16 HR, 63 RBI stat line. After a decent encore in 1963, the 36-year-old showed his age the following year. In June, with his average at .222 and yet to hit a longball, Vic was traded to the Angels as part of a three-team deal. After batting .249 with 3 home runs in 68 games in L.A., he was shipped to the Phillies in September. You may be wondering why the card above has an Angels pennant and logo, in that case. As it so happens, the Halos reacquired Power in November, allowing Topps to use a photo of him that they'd ostensibly taken in the summer of '64. By that time, he was completely unable to live up to his name, stroking just nine extra-base hits in 197 at-bats in 1965. When the Angels released him the following April Fool's Day, it was a wrap for Vic Power. He carried a .284 batting average for his career.

The four-plus decades since Vic's career ended have cemented his legacy as one of the trailblazing Latin American players in Major League Baseball. He moved back to his native Puerto Rico and instructed future major leaguers such as Roberto Alomar, Jose Oquendo, Jerry Morales, Willie Montanez, and Jose Cruz, Sr. In 2005, just months after sharing memories of his career in the American documentary

Beisbol, 78-year-old Vic Power succumbed to cancer.

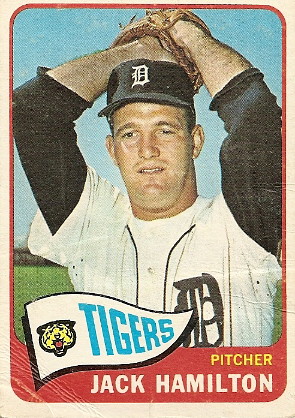

Fun fact: Vic is one of 11 players to steal home plate twice in a game, having performed the feat on

August 14, 1958. His first swipe gave the Indians a 9-7 lead in the eighth inning. After the Tigers tied the game in the ninth, Power stood on third in the bottom of the tenth with the bases loaded, two outs, and Rocky Colavito at bat. He took advantage of pitcher Frank Lary's struggles, breaking for home and catching him unaware with the game winner!