Wow, it's been a while since I got to write about an Oriole on this blog, and today it's one of the all-timers.

Milt Pappas was born in Detroit as Miltiades Sergios Pappastediodis. If I were him, I probably would have wanted to shorten my name too!

As a high school phenom, young Milt was heavily scouted and pursued by his hometown Tigers. But it was an ex-Tiger pitcher, Hal Newhouser, who scouted the righty and was instrumental in his signing with the Orioles. Detroit was furious, convinced that the Birds had skirted the rules. They filed an unsuccessful greivance, but later caught the O's red-handed when manager Paul Richards tried to stash a healthy Pappas on the disabled list while having him travel and practice with the club.

The wily Richards made Pappas into his pet project, including placing him on a strict pitch count (which was unheard of at that time). The veterans on the team were rankled by this, and Milt's cocky attitude didn't help matters. But he was undeniably talented, all but bypassing the minor leagues and winning ten games in 1958, his first full season in Baltimore. He had excellent control, never walking more than 83 batters in a single year. He combined with Steve Barber, Jack Fisher, and Chuck Estrada to form the "Baby Birds" rotation, and twice led the team in victories. In eight seasons with the O's, he was a double-digit winner every year, and notched three All-Star selections: two in 1962 (12-10, 4.03), and another in 1965, which may have been his best campaign (13-9, 2.60). His 110 career wins as an Oriole still rank seventh in team history.

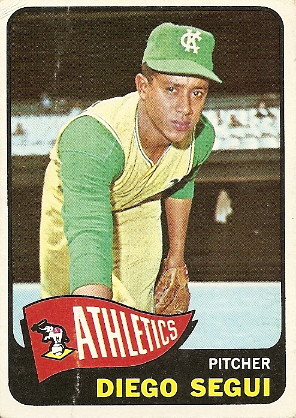

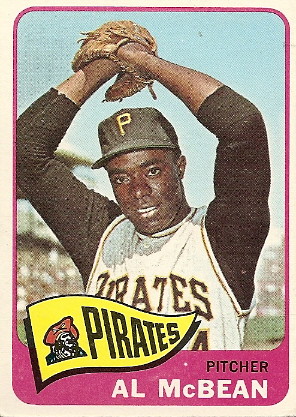

In December of 1965, Pappas gained notoriety in baseball role. The Orioles took advantage of Cincinnati's predilection for trading players before their decline rather than after. The Reds traded 30-year-old slugger Frank Robinson to the O's for Milt and two other players. Frank hit the ground running, winning the A.L. Triple Crown and leading his new club to their first World Series win over the Dodgers. Meanwhile, the Reds' supposed new ace lasted just two-plus years in his new digs, posting a career-worst 4.29 ERA in 1966 before rebounding to go 16-13, 3.35 the following year. However, Pappas' outspoken nature was what truly made him expendable. He feuded with fellow pitcher Joe Nuxhall, who claimed that the former was milking injuries. In turn, Milt complained that Nuxhall (after retiring to the broadcast booth) was flying first-class while the players were stuck in coach. He also criticized the Reds for failing to cancel a scheduled game on the day of Robert F. Kennedy's funeral. A slow start in 1968 (2-5, 5.60) was the final nail in the coffin, as Pappas was traded to the Braves.

Milt regained his form in Atlanta, winning ten games and putting up a strong 2.37 ERA. His final win of the year was his 150th. He was one of 16 modern-era pitchers to compile 150 victories prior to age 30; the only man on that list to make it to 300 wins was Greg Maddux. Pappas slumped to 6-10 in 1969, but did see postseason action for the only time in his career. Pitching in long relief, he surrendered three runs in two and one-third innings in the Braves' 11-6 loss in Game Two of the NLCS. Another poor start to the following season led to another change of zip code, with the Cubs purchasing his contract.

Again, Milt found equal parts glory and controversy in his new locale. He was a ten-game winner in his first half season in Chicago, and actually performed better in hitter-friendly Wrigley Field than he did on the road. In 1971, he won a career-high 17 games and tied a major league record with a nine-pitch, three-strikeout inning against the Phillies in September. He was even better the next year, going 17-7 with a 2.77 ERA. But on

September 2, he threw the greatest game of his career, retiring the first 26 Padre batters he faced. San Diego's last hope was pinch hitter Larry Stahl, who took two straight pitches with a 2-2 count. Home plate umpire Bruce Froemming called both offerings balls, sending Stahl to first base and disrupting the perfect game. The pitches were both borderline sliders, and Pappas went ballistic, thinking that he was at least close enough to get the benefit of the doubt in that situation. He retired the next hitter to preserve his no-hitter, but has maintained a grudge against Froemming throughout the ensuing decades.

A year later, Milt concluded his career with a 7-12 season, bringing him to 209-164 with a 3.40 ERA. Despite intimations from teammates that Paul Richards' pitch limits conditioned Pappas to hit a mental wall late in games, he did complete 129 of his 465 starts. He also finished one win short of joining the short list of pitchers to rack up 100 victories in each league.

Fun fact: Milt had some power in his bat, amassing

20 career home runs, half of which gave him the lead!